Do you believe that competence in yesterday’s role is a viable reference for suitability for the new one? If you do, you’re not alone; however, in practice, that belief often backfires. It’s called the Peter Principle.

This article unpacks why even the smartest technologists can plateau at the top, how that plateau affects product vision and team morale, and—most importantly—what practical steps you can take to ensure your own (and your organisation’s) ascent doesn’t end on an accidental ledge.

Coined by Canadian educator Laurence J. Peter in 1969, the Peter Principle states that in a hierarchy, people are promoted according to success in their current job until they reach a role whose demands exceed their competence. There, they “level off,” and overall organizational performance suffers. Modern management literature still finds statistical evidence for the effect.

You promote your star engineer: “Congratulations, you’re now Head of Engineering.” Six months later, sprint velocity is erratic, architecture decisions stall in endless meetings, and your best people are updating their LinkedIn profiles over lunch.

That’s the Peter Principle in action. A quiet drift from individual brilliance to organisational drag, where competence in yesterday’s role becomes insufficiency in today’s.

| Amplifier inside tech organisations | Why does it magnify the Principle |

| Skill‑set discontinuity between “maker” and “manager” | A Staff Engineer’s day‑to‑day excellence is deep technical problem‑solving; a CTO’s is portfolio governance, finance, security risk, and board influence—all largely orthogonal skills. (source: CTO Academy) |

| Rapid growth & title inflation | Startups can double in size every 12 months, creating “overnight” VP/CTO vacancies that outpace leaders’ development. |

| Hero culture & scarce senior IC tracks | When the only perceived way to reward top engineers is to make them managers, talented ICs (Individual Contributors) are nudged onto the wrong career path, leaving them and their teams exposed. (source: Forbes) |

| Obsolescence velocity | Tech stacks, threat models, and delivery practices shift every few quarters; the gap between yesterday’s hands‑on expertise and today’s strategic requirements widens fast. |

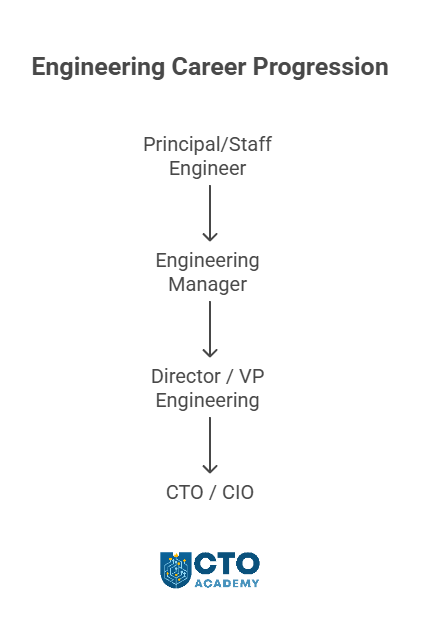

Here’s the problem: If developmental support lags at any step, the leader can plateau at a “role of incompetence.” The symptoms include:

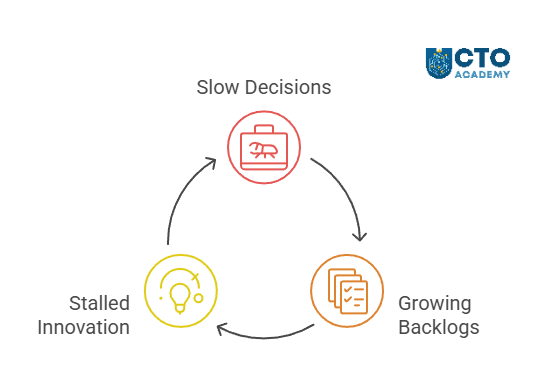

When a leader hits their “level of incompetence,” the organization rarely implodes overnight; instead, momentum leaks away in a thousand small, compounding delays—what seasoned operators call execution drift. Here is what that looks like in a technology organization:

| Manifestation | What you observe on the ground | Why does it happen under the Peter Principle |

| Decision latency | Architectural choices linger in “review” for weeks; cross‑team trade‑offs bounce between meetings without closure. | The new exec lacks the contextual breadth—or confidence—to weigh risk quickly, so they defer or seek consensus on every choice. |

| Backlog inflation | Tickets age out of active sprints; “fast‑follow” features accumulate until road‑maps resemble wish‑lists. | Prioritization demands a product‑level mindset, but a technically‑anchored leader keeps adding scope rather than negotiating it. |

| Release cadence decay | Deployment frequency falls, hot‑fixes multiply, and DORA metrics trend the wrong way. | Teams compensate for indecision with parallel work streams, creating merge hell and longer integration windows. |

| Technical debt creep | Shortcut fixes become the norm; refactor budgets disappear; incident post‑mortems repeat the same root causes. | A leader who once thrived on heroic coding now rewards speed over system thinking, eroding quality. |

| Innovation stall | Hackathons turn into “bug‑bash” days; patents, proofs‑of‑concept, and new‑stack evaluations dry up. | Energy is spent firefighting the drift, leaving no cognitive or calendar space for forward‑looking bets. |

Left unchecked, execution drift silently erodes competitive advantage:

What begins as a leadership skills gap becomes a systemic drag on valuation, security posture, and customer satisfaction.

Execution drift is reversible—but only if diagnosed early. Therefore, watch decision velocity as closely as burn rate, and pair newly promoted tech leaders with mentors, OKR‑driven scorecards, and empowered lieutenants who can keep the delivery engine humming while leadership skills catch up.

High‑calibre engineers leave when they feel “managed” by someone who no longer understands their craft.

CTO Academy

When a tech leader plateaus, they rarely lose everyone at once. Instead, the company steadily bleeds skilled people. Top engineers—those who joined to solve hard problems alongside respected peers—begin to feel “governed” rather than “inspired,” and they quietly plot an exit. This is talent attrition in the Peter‑Principle era.

| Manifestation | What you observe on the ground | Why does it happen |

| Senior departures spike | Staff‑ and Principal‑level résumés hit LinkedIn; exit interviews cite “lack of technical vision.” | Elite ICs lose confidence in leadership’s grasp of modern engineering and seek environments where their craft is valued. |

| Engagement dips among core contributors | Participation in design reviews and architecture guilds drops; voluntary brown‑bag sessions dry up. | When feedback from experts is ignored or misunderstood, they disengage before they resign. |

| Shadow decision‑making emerges | Influential engineers hold informal “hallway summits” to bypass official channels. | They trust peers more than the leader for architectural guidance, creating unofficial hierarchies. |

| Escalating compensation demands | Remaining talent asks for outsized raises or retention bonuses. | Money becomes a proxy for the recognition and autonomy they no longer receive. |

| External thought‑leadership shifts | Once‑active engineers now speak at conferences about life after big‑co burnout. | Public narratives signal to the market that your engineering brand is fading. |

Talent attrition is the silent saboteur of delivery velocity and culture:

Preventing Peter‑induced attrition demands visible, credible technical stewardship at the top:

Treat attrition metrics with the same urgency as uptime SLAs because by the time the resignation emails hit HR, the knowledge has already walked out the door.

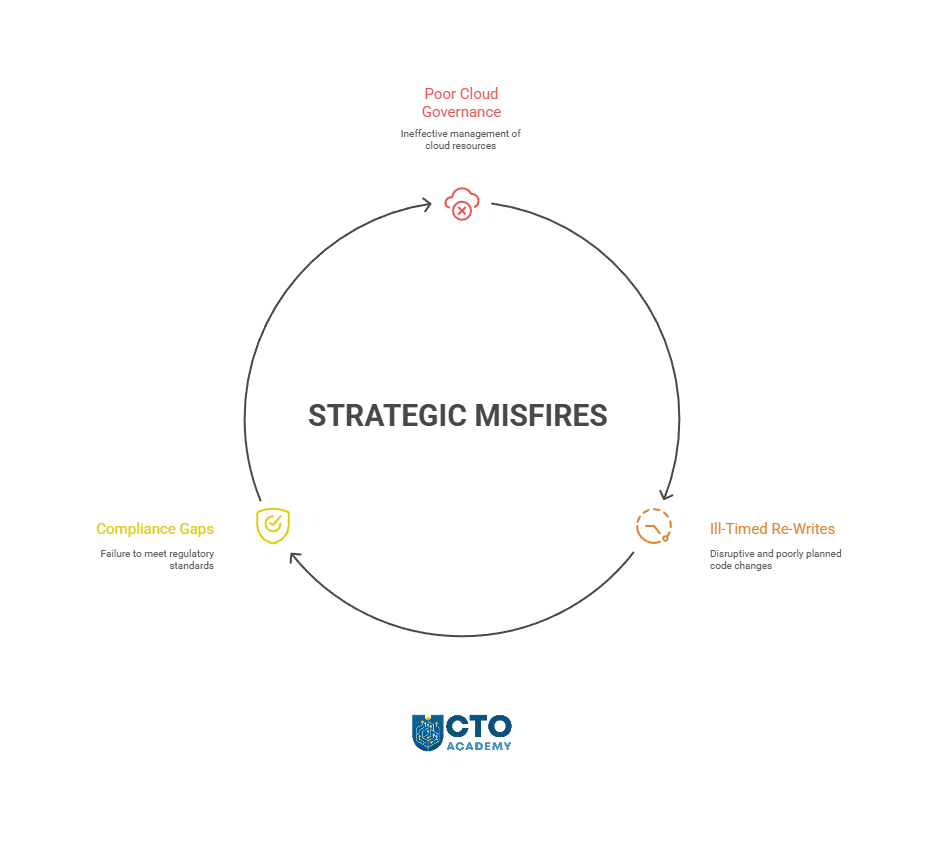

At senior levels, the damage caused by the Peter Principle shifts from day‑to‑day friction to board‑level blunders. A leader whose competence topped out two rungs below the C‑suite can steer the entire organisation into strategic misfires—expensive, reputation‑risking decisions whose consequences linger for years.

| Manifestation | What you observe on the ground | Why does it happen under the Peter Principle |

| Exploding cloud spend | AWS/GCP invoice grows faster than revenue; sudden “cost‑freeze” edicts halt feature work. | A leader versed in code efficiency, not cloud economics, overlooks reserved‑instance planning, FinOps tooling, and usage governance. |

| Ill‑timed platform rewrites | Multi‑year “greenfield” projects consume half the engineering headcount, delaying market features. | Comfort zone bias: the exec defaults to large‑scale rebuilds (a familiar technical challenge) instead of incremental modernisation aligned to business value. |

| Compliance and security gaps | SOC 2 renewal slips; new data residency rules caught late; security controls lag industry baselines. | The role demands legal, privacy, and risk fluency, but the leader’s expertise is still in architecture diagrams, not regulatory landscapes. |

| Vendor lock‑in or tool sprawl | Dozens of overlapping SaaS contracts; migration away from proprietary services becomes cost‑prohibitive. | Insufficient vendor‑management acumen leads to tactical purchases without long‑term integration or exit planning. |

| Misaligned M&A tech diligence | Acquired product’s code base turns out to be unscalable, requiring unplanned overhaul. | The leader lacks the due diligence checklist and cross‑functional perspective needed for acquisition‑level decisions. |

Strategic blunders are preventable when technical brilliance is matched with business acumen:

By treating strategy as a discipline—one that fuses technical insight with financial, legal, and market perspectives—organisations can inoculate themselves against the costly missteps that surface when leadership outgrows its depth.

Empirical studies show that top performers promoted merely for past results underperform as managers, validating Peter’s hypothesis in modern data sets.

| Level | Organisational action | Why it works |

| Before promotion | • Assessment centres simulating planning & feedback conversations• “Acting” lead roles on a single project | Low‑risk proving ground for leadership aptitude. (source: CTO Framework) |

| Parallel ladders | Staff‑, Principal‑, Distinguished‑Engineer tracks with comp parity to managers | Retains technical stars without forcing them to manage. (source: Forbes) |

| Structured development | Executive coaching, MBA‑style tech‑leadership programs, CTO peer networks | Builds budgeting, storytelling, and governance muscles before they are mission‑critical. (source: CTO Academy) |

| Continuous calibration | 360° feedback, OKR, or V2MOM scorecards measured at the org rather than the code level | Surfaces gaps early; allows course‑correction or lateral moves. |

| Flexible career “portfolios” | Non‑linear moves—e.g., product, security, customer success stints | Broadens context; avoids one‑way ladders. (source: Harvard Business Review) |

The Peter Principle is not destiny; it is a risk signal.

In technology organizations—where the leap from coding to capital allocation is especially wide—intentional career‑architecture, robust dual‑track ladders, and early leadership skill‑building are the antidotes. Done well, they keep brilliant technologists brilliant and ensure that those who do rise to the C‑suite arrive equipped, not exposed.

90 Things You Need To Know To Become an Effective CTO