A recent survey of 260 global CTOs found that 91% identified tech debt as a ‘major concern’ whilst issues such as cybersecurity, employee turnover and budget restraints registered less.

In this article, we take a deep dive into tech debt with contributions from five senior technology leaders across the CTO Academy community. They will provide their perspective on the problem and potential mitigation strategies towards the solution.

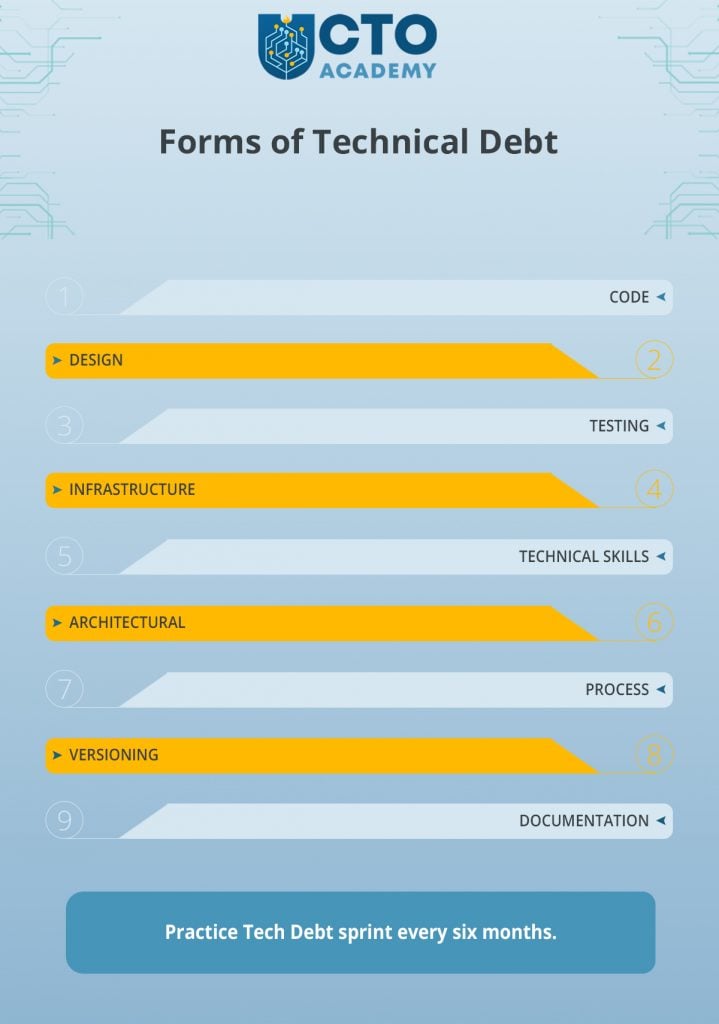

“Tech Debt sprint every six months”.

Jason Noble, CTO Academy, London

I’ll start with a ridiculously simple example.

Last week, we had to put some external code on our website.

The new website manager put it directly into the template so it would load on every page. However, we have other external code on our website which is inserted via Google Tag Manager. So I insisted the new manager move the code from the template to GTM (with a bit of grumbling!).

If he had not moved the code to GTM immediately, it would have become technical debt. In other words, something which was simple to fix on the spot would become more challenging in a week as one would have to refresh one’s memory as to the problem.

How many of these simple examples does it take? 10? 50? How many before we end up with substantial technical debt on our hands making the website difficult to manage?

Let me open this discussion by detailing various forms of technical debt.

Code Debt

When code is not properly written or structured, often due to rushing to meet deadlines, we have a code debt. It can lead to a codebase that is difficult to read, maintain or extend. Examples include duplications, large classes or methods and lack of modularisation.

Design Debt

It arises when a software design is flawed or becomes outdated. Design debt manifests in systems that are hard to scale or modify. Poor design choices, such as not following design patterns appropriately or over-engineering, contribute to this debt.

Testing Debt

Skipping or rushing testing phases can lead to insufficient test coverage or ignored failing tests. This debt increases the risk of bugs and failures in production.

Infrastructure Debt

When the development or production environments are not properly set up or maintained, we end up with infrastructure debt. This can include using outdated tools or platforms, inadequate server capacity or lack of automation.

Dependency Debt

Comes from relying on outdated or unsuitable third-party libraries and tools, leading to security vulnerabilities, compatibility issues and limitations in functionality or performance.

Technical Skills Debt

This form of debt arises when the team lacks the necessary skills or knowledge to work efficiently with the current technology stack or to implement best practices. This often leads to suboptimal solutions and increased maintenance work.

Architectural Debt

It is similar to design debt but at a higher level. Architectural debt involves issues with the overall structure and interaction of different parts of the system, leading to difficulties in scaling, integrating new features or adapting to new requirements.

Process Debt

Process debt is generally caused by inefficient or outdated development processes. Examples include lack of agile practices, poor communication between team members or inadequate project management.

Versioning Debt

When software components are not kept up to date, versioning debt leads to compatibility issues, security vulnerabilities and increased effort required for future updates.

Documentation Debt

Insufficient or outdated documentation makes it harder for new team members to understand the system and for existing members to remember why certain decisions were made. Unfortunately, most technical documents go out of date the moment they’re written.

I have always been conscious of technical debt and tried to keep it to a minimum during my career. Code must be well maintained, systems kept up to date (including operating systems) and redundant systems/code removed. Finally, I make sure there is a sprint every six months allowing teams to tidy up so that it never builds up to something unmanageable.

“Not all technical debt is equal”.

John Cleary, Fractional CTO, Manchester

When discussing technical debt, especially with non-technical leaders, I always ensure that we have a shared understanding of what we mean by ‘debt’ — ie, we take some shortcut today that we have to repay at some point in the future.

The cost of not repaying that debt results in ‘interest payments’ which translates to either software or infrastructure that is harder to work with and, therefore, costs the business more to deliver every new feature.

Every project has some technical debt, but not all technical debt is equal.

For example, you may have a particularly unruly module in your codebase that is a real pain to work with. But if it hardly ever gets touched, then the effort to refactor it may far outstrip any potential benefit you expect to receive from paying down that debt.

Therefore, understanding the impact of the debt on your teams’ productivity (and happiness) is essential. I’ve always encouraged teams to maintain a list of their worst bugbears which should be prioritised based on two factors:

Allowing some time either in each sprint or setting aside a whole sprint every few months to tackle these issues will help keep technical debt under control.

I mentioned happiness above, and while it might at first sound odd to talk about developer happiness when discussing technical debt, many developers need to know three things.

First, you take technical debt seriously.

Second, you care about quality.

And, ultimately, third, you listen to and trust them to make recommendations that affect the thing they do every day in service of your business.

Ignoring technical debt for too long can lead to a negative spiral where new features take longer and longer to deliver. Consequently, team members, feeling frustrated and ignored, start looking around for new roles. Often, the strongest team members leave first, causing a sort of ‘brain drain’ on the rest of the team. This inevitably results in further slow-downs, and so on.

Good people won’t stick around for long if they feel that tech debt is something we’ll tackle ‘one day when there is more time’. In other words, a quieter day is not coming, so start putting time aside now. It’s sound economics and it will also make your team happier.

“A definite rigour can be applied.”

Ken Kolchier, CTO of Trade Technologies, specialising in optimising engineering organisations

With Jason having identified categories of tech debt to look for, we are in a position to assess any one of them for priority, cost to remedy and cost to leave alone.

Tech debt will, by necessity, always exist and accumulate. In software, we make directional decisions about where to add complexity to account for likely change, and where to implement stability and opinionated design.

Regardless of the type of debt, business forecasting the cost of handling or not handling specific debt can be critical to prioritising the right things. Forecasting and managing this area can sometimes be more art than science, but there is definite rigour that can be applied.

Most of us are well aware that tech debt stems from not designing enough adaptability in a highly changing area. On the other hand, coding too much flexibility in a slow-changing area is, de facto, tech debt in its own right. That is, whenever we might need to change that code, the complexity of pre-designed adaptability adds friction and possible instability.

When assessing code or design debt, typical (and atypical) codebase analytics involve scanning with tools such as Sonarqube, JetBrains Qodana, NDepend and others. Additional insight might be gained from other data, such as crunching numbers from the git log to map hotspots in the code to levels of debt.

The hotspot metrics are not only a factor to include in calculations but can also help us quickly decide when ROI simply isn’t there, and to stop analysing.

The team – and we as technical leaders – might feel a certain area is riddled with tech debt and needs to be addressed. Yet, if the system is stable and working in that section and the code is rarely touched, it shouldn’t rise as a priority.

For most metrics, we can get fairly good ballpark numbers about the cost of change or how many team hours are required to add test coverage to one line of code; fix one duplicate block or simplify one largely complex file.

We can apply these numbers to the debt metrics we’ve gathered, quantifying how much it would cost to remedy it in the specific component we’re analysing. But do make sure to include all the various factors — complexity, code issues and test coverage. This helps to reach a balanced assessment as code that is low in complexity and also low in test coverage might not be prioritised, as the impact of any tech debt is easily navigated later.

Along with the cost to address the debt, we need the other side of the coin —

Granted, gathering this information can take some finesse. However, we can start with a solid analysis of how long our tickets or tasks take to complete in the code area in question. Survey the team to guesstimate how much faster those tickets might be completed if the debt were removed.

We can now easily generate a cost/benefit analysis, calculating the current cost of the friction by the following formula:

How much time would be saved per ticket x The dollar cost of our team completing one ticket x The average number of tickets in a given cycleAnd then compare that to the previously gathered cost to remedy.

Combine this with priority based on hotspots, and we have a well-rounded picture.

Other areas such as testing debt can be analysed similarly. We can track the difference between bugs that are ‘escapes’ (bugs in newly changed code) versus bugs in legacy areas of the code and prioritise them accordingly.

Applying this kind of rigour not only helps us and the business make good decisions, but our teams can respond to it as well. We’re simply helping them see quantified, engineer-type numbers around what is usually a very fuzzy answer to a fuzzy question.

“It needs strategic handling”.

Sid Mustafa, Fractional CTO and founder of Phoenix Consulting

In my tenure across diverse software engineering roles, I’ve encountered technical debt in various forms. It’s a nuanced challenge that needs strategic handling and I believe it is neither good nor bad.

For instance, at one company I worked at, we faced tech debt as a consequence of a lack of organisation, planning and prioritisation. The business was operating as a feature factory.

To improve the state of affairs, we had to judiciously decide if and when to incur this debt for agility. Additionally, we had to decide when to allocate resources for its reduction.

At another company, rebuilding the codebase demanded a delicate balance between rapid development and long-term sustainability.

Here, technical debt was a strategic choice and an important consideration for maintaining a robust, scalable product.

In addition to these strategies, we also employed a tool called Stepsize in our IDE. This tool significantly streamlined our technical debt management process. Stepsize allowed us to log technical debt more naturally as we worked, embedding the process into our daily development activities without causing significant disruption or context switching.

By tagging technical debt items with impact and priority labels directly within our development environment, we reduced the cognitive load on the team. This approach enabled us to handle mundane tasks efficiently while maintaining a comprehensive and prioritised log of our technical debt.

The integration of Stepsize into our workflow was a game-changer, allowing for a more fluid and less intrusive method of tracking and managing technical debt, ultimately contributing to our team’s increased productivity and focus.

After implementing a robust prioritisation and planning process to manage technical debt, we observed a 20% increase in deployment frequency and a 15% reduction in the time taken to transition from code commit to production.

However, after integrating the Stepsize, we observed a 75% reduction in the time developers spent on identifying and logging technical debt.

It was also central to the decreased cognitive load on the team when working around TD and significantly improved DevEx.

Technical debt extends beyond code; it permeates the wider business, impacting architecture, product features and customer/team satisfaction. To effectively manage it, a structured approach is essential. This includes:

By doing so, we can use it strategically to accelerate development without falling into an unrecoverable debt spiral.

Moreover, the categorisation of technical debt is crucial for efficient management. Utilising frameworks like the technical debt quadrant or the 13 distinct types identified by the Software Engineering Institute — architecture, build, code, defect, design, documentation, infrastructure, people, process, requirement, service, test automation and test debt — provides a clear structure for prioritisation and handling.

“Name it, visualise it, prioritise it”.

Pawel Slotorsz, DevOps Manager at Hard Rock Digital, Poland

In my view, the term tech debt refers to the lack of ability of an organisation or team to adapt and respond quickly to changes, challenges and opportunities in the rapidly evolving IT landscape.

I have encountered tech debt in all projects that I have participated in and observed it from a distance in other teams.

Jason has provided some very good examples, and my experience has been very similar. But let me add my take on the most common causes of tech debt which recur from company to company and project to project.

An organisation decides to buy or lease a third-party codebase or platform to speed up the delivery of the product or service. Although feature- and market-wise the organisation compares several options and picks the best solution, they accept the fact that, for example, the tech stack will not fit into current modern tech architecture; eg, cloud-native, Kubernetes, serverless, development frameworks or others.

In the above case, most of the time, the tech debt is created literally from the moment the engineers write the first line of code and the code is pushed to the repository. This happens because it is impossible to predict all the consequences of using a particular solution. It is also connected to a lack of skills in the engineering team.

Alternatively, engineers will often manage the issue by repeating a previous fix to a similar problem. Why? “Because”, they say, “it’s always been done this way”.

The aim is to free up teams or individuals and speed up delivery. But the inevitable outcome is tech debt. If that debt is not properly managed, it will decrease productivity, increase maintenance costs, reduce software quality and, ultimately, bring about the failure of the project.

Start by acknowledging that tech debt is there. Name it, visualise it and prioritise it.

This can be done in several ways. I’ve done it via a risk register, backlog refinement, proof of concepts and R&D.

The first two can answer questions such as:

R&D provides the opportunity to research solutions, innovate or learn from others.

Therefore:

1) Allocate a percentage of your time and money to:

In some cases, you’ll need a strike group — a team for whom dealing with the most urgent areas of debt will be a priority.

2) Measure the following:

3) Determine whether too much or not enough of your workforce is dedicated to dealing with tech debt problems and whether allocating those resources is blocking the business from operating efficiently. Remember, it’s always about proper balance. The time and effort needed to deal with technical debt won’t be constant.

4) Resist the use of fancy tech when there is no use case or business value for it. And always learn from other teams, organisations and people in your network about how they manage the problem.

It’s a challenge most of you are dealing with so I hope we’ve helped provide some answers.

Thanks to everyone who contributed to this article.

What are your experiences with tech debt?

Do you agree/disagree with the problems and solutions raised here? Let us know.

90 Things You Need To Know To Become an Effective CTO

London

2nd Floor, 20 St Thomas St, SE1 9RS

Copyright © 2024 - CTO Academy Ltd